[Maya] Writing 3D Poisson Disk Sampling Entirely In MEL Because I Can

Visualization of a 2D Poisson Disk sampling distribution, courtesy of wikipedia

Preface

Is Maya’s MEL scripting language really meant for writing sophisticated algorithms? No, is the short answer. The lack of support for several things you’d find in Python makes the latter a much more attractive option for writing algorithms and high level code. Indeed, the typical approach is to use Python or PyMel to write your Maya scripts; MEL is mostly there for legacy reasons, but is good to know in understanding how Maya operates.

MEL

So what makes MEL a worse option than Python in most cases? Frankly, the language is just cumbersome to write, its interpreter is fairly dumb compared to Python, and it doesn’t have a lot of features you’d find in modern languages, like arrays of arbitrary dimensions, or the ability to define your own data structures.

So what better way to

wastespend time than to write a 3D Poisson Disc Sampling algorithm entirely in MEL?

Why? Because I thought it’d be an interesting challenge to do while familiarizing myself with MEL, and because I can.

Poisson Disc

I won’t explain what the Poisson Disc Sampling in too much detail, you can read more about what it is and how to generate it in this paper, which I take inspiration from.

What it is

In short, Poisson Disk Sampling is an algorithm that produces points that are tightly packed, but no two points are closer than a minimum distance from each other. Though the example at the top of the page shows 2D points, Poisson Disk Sampling can be in any arbitrary dimension, at least with the method proposed by Bridson in the paper I linked above.

Challenges

In vanilla MEL in Maya 2024, we have the following restrictions:

- Our only data types are:

stringint, floatvector3matrix2D

- No external libraries

- Critically, this means no hash tables out of the box.

- No user-defined data structures

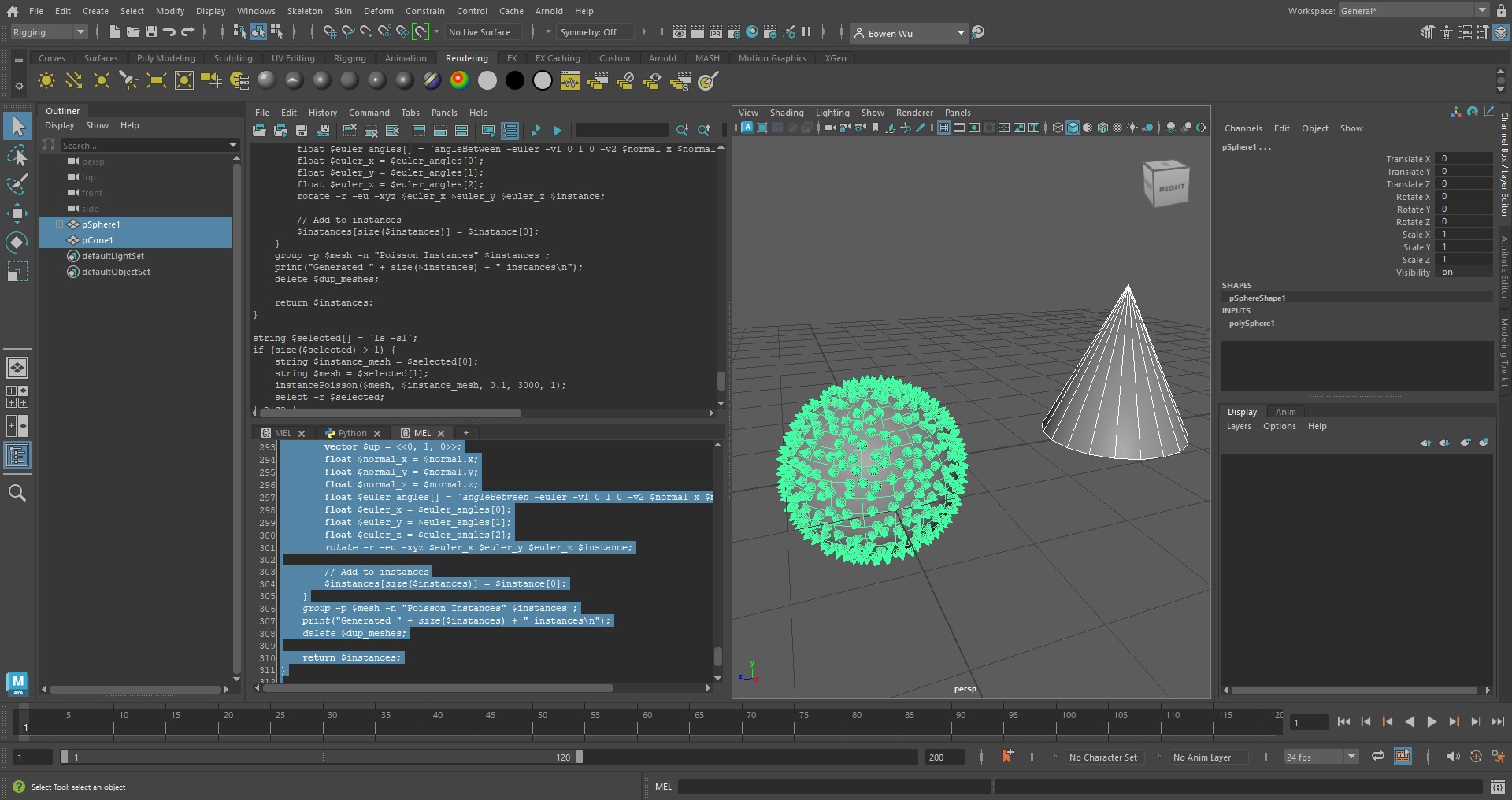

Instancing cones on Poisson Samples on a sphere

Implementation and Reflection

Was this worth my time? Probably Not

Was this practical? Absolutely Not

Did I learn something new? Absolutely Yes

To be honest, writing it all in MEL was much more painful than I thought it’d be, the language was simply not made to handle this kind of work. I probably could have written it in half the time in Python.

Not having access to user-defined data structures was a major pain, since now I have to deal with separate arrays of different data types instead of one nicely structured custom data type.

Getting around the lack of hash tables was also difficult, what I ended up doing was to try to use array indices as the keys for my data. It definitely wastes memory in some places since I didn’t need every element that was allocated for what I need, but it was necessary.

As for what I’ve learned, well I’ve definitely gotten a taste of writing MEL now; perhaps a bit too much. Learning how to randomly sample a triangle uniformly with just two numbers was rather neat (section 4.2 of this paper), I’m sure I’ll find it useful at some point in the future.

Since I’m trying to generate points on a 3D mesh, I couldn’t follow the paper exactly, since there’s the constraint that the points would have to lie on the mesh surface. So instead, I opted for a naive dart throwing algorithm to generate my samples. Computing geodesic distance was also not in the scope of what I intended, so I opted to just use Euclidean distance to get it to work.

If I were to actually have to use what I wrote, I would definitely try to implement geodesic distance computation on the mesh for a sampling distribution that would be correct for any mesh. Of course, I would also write it in Python.

Source Code

I’ve included my source code here. It’s a bit messy and disorganized. mesh_poisson can be copy and pasted into the script editor, and ran with the object to instance and object to instance onto selected, in that order. poisson contains an implementation that more closely follows Bridson’s paper, but only generates 2D points.