[Blender 3.6] Geometry Node Screen-Space Inverted Hull Outlines

Table of Contents

- Blender 3.6 Update

- Preface

- Simple Inverted Hull in Blender

- Geometry Node Based Inverted Hull

- Implementation Time!

- Download

Blender 3.6 Update

In the old version of this post, you’d need to re-setup the drivers to retrieve scene data whenever you want to use it in a new file simply due to Blender’s limitations with it comes to linked libraries and drivers.

However, with Blender’s 3.6 update, Drivers now can use context properties, which allows a driver to implicitly reference the active scene or view layer. This allows us to set up these drivers once in the asset file, and reuse them via library links without additional setup.

This update makes the geometry nodes easier to setup. Since I’ve also made a couple of minor changes since I wrote the old version, I’ll also include them here, as well as explaining more things in depth.

Preface

In stylized realtime rendering, one quick and easy way to achieve outlines is the Inverted Hull method; the mesh is duplicated, each vertex offset along the normal, and is rendered via a back-face-only material with a solid color. You can see this employed by Arc System Works in their 3D anime fighting games such as the recent installments of the Guilty Gear series.

It should be noted that this isn’t the only nor best way to achieve realtime outlines, as it cannot handle all types of outlines, and has artifacts in specific scenarios. For better methods of outline extraction, please refer to this excellent article by Panthavma

Look closely on the outlines, and you can see how it follows the polygons. This is especially evident on Sol's left deltoids.

Simple Inverted Hull in Blender

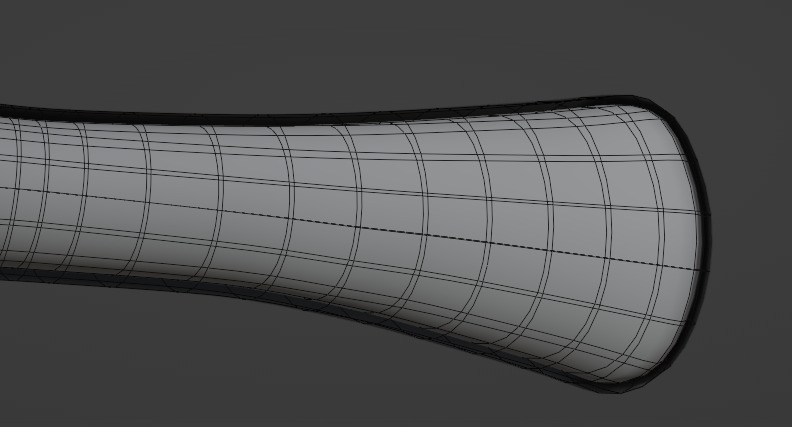

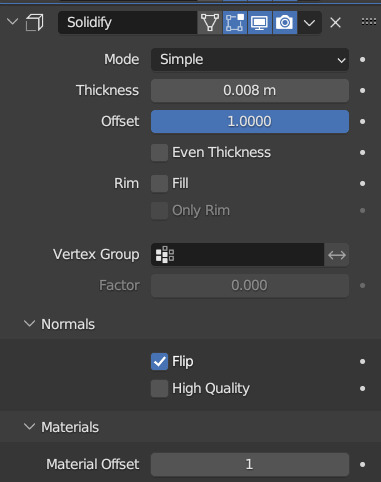

In Blender, the easiest way to achieve this is to use the Solidify modifier with flipped normals and a material that only renders the back-face.

The mesh has an outer shell, which is the Inverted Hull outline. Notice that we have Material Offset set to 1, meaning the solidified mesh will use the second material slot assigned to the mesh, which is a black emissive material that only renders its back-face.

However, this has limitations:

- The modifier can only act on one mesh at a time, making managing this on a multi-mesh character, or an entire scene, difficult without building additional tooling.

- The modifier has a uniform value for how far to extrude the outline mesh. Meaning the outline thickness is defined in world space.

- This can be attenuated with vertex weights, but modifying vertex weights in real time is bit of a pain in Blender, and we can only use values between 0-1

- At extreme angles, world space outline thickness makes the closer part of the mesh appear to have a thicker outline than the rest of the mesh.

- Though depending on art direction, this could be desirable.

The hand's outline is significantly thicker than the objects behind it, and the outlines on the button are clipping as well

So how do we do this?

In order to achieve a more consistent and uniform Inverted Hull result, we must redefine its thickness in screen space. Normally in a game engine, this is easy to do: you’d implement Inverted Hull in geometry shaders, with the vertex shader passing in the screen-space/clip space matrix for you to then perform Inverted Hull calculations.

Unfortunately in Blender, we do not have access to the vertex or geometry shader, nor do we have access to any matrices outside of Python scripts. So here’s where Geometry Nodes come in.

Geometry Node Based Inverted Hull

With Geometry Nodes, rather than only being able to extrude the Inverted Hull cage along its vertex normal, we can specify exactly how we want it to move. With some simple vector math, we can achieve a result that gets you a much more uniform Inverted Hull thickness within screen space. This means that the outlines stays consistent regardless of your camera’s rotation and location; allowing you to set and forget then carry on with the rest of your animation. Though, having uniform outlines for everything can make your renders look monotonous and boring, so we will also add more controls to customize its behavior. Plus, we can organize the nodes such that every outline can be controlled from one (or arbitrary many) places.

Now the entire model's outline is much more uniform, with the buttons looking much better too

Realtime Demo

The outline of every mesh can be controlled by changing the property of a single Geometry Node graph (Note: the node group inputs here is an older version)

The basic principle

So the idea is to take our vertex normal vector, project it such that it is parallel to the near-plane/far-plane of the camera, then scale it by a factor such that it will be the length that we want it to be in screen space, and finally projecting it back to the original normal vector while preserving its screen space length. We then create the inverted hull mesh using these new vectors, rather than just the normal vectors in the traditional method.

So that was a mouthful of words, which probably wasn’t too helpful to many people. So here’s a more visual demonstration, where the arrows represent the vectors we’re calculating for the inverted hull mesh extrusion.

- The first transform is projecting the normal vectors to be parallel to the camera’s near/far plane.

- Then we scale the vectors such that they’re the same size in screen space.

- We re-project the vectors back onto the original normal vectors while maintaining their screen space size. This is to avoid artifacts from the shell clipping with the original model.

From the camera’s point of view, the last step doesn’t look like the vectors have changed direction or length at all, which is what we want.

The vector arrows' shading still changes slightly due to them moving towards/away from the perspective camera in 3D space still

Implementation Time!

1. Project Normals to Camera Plane

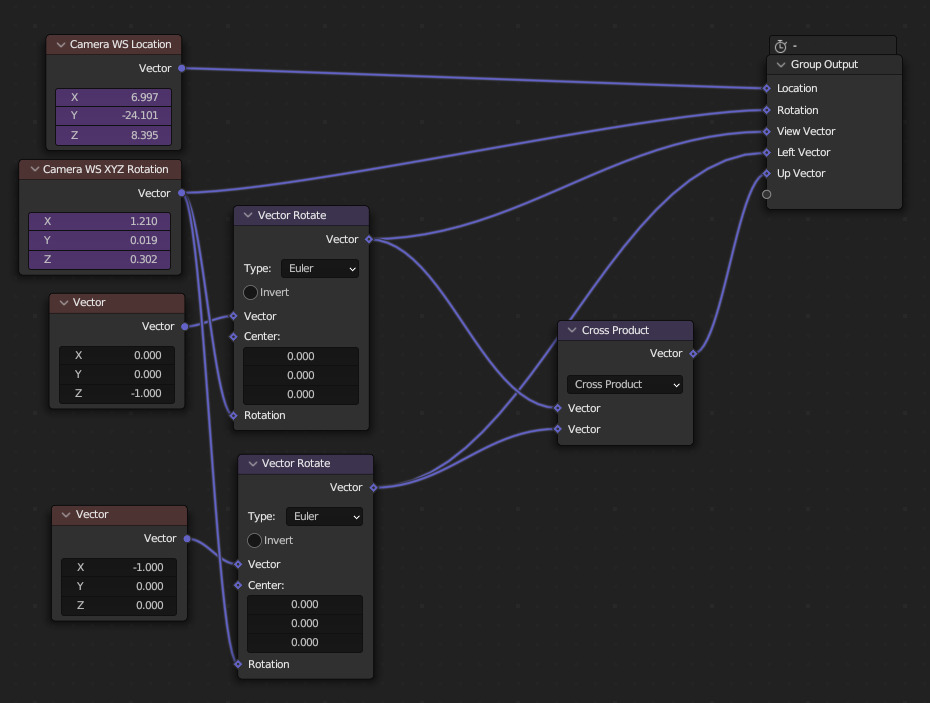

First we need to retrieve data about the active camera with the following node setup to obtain its world space location, XYZ euler rotation, as well as basis vectors.

We make use of context properties obtain the active camera's world space location and rotation.

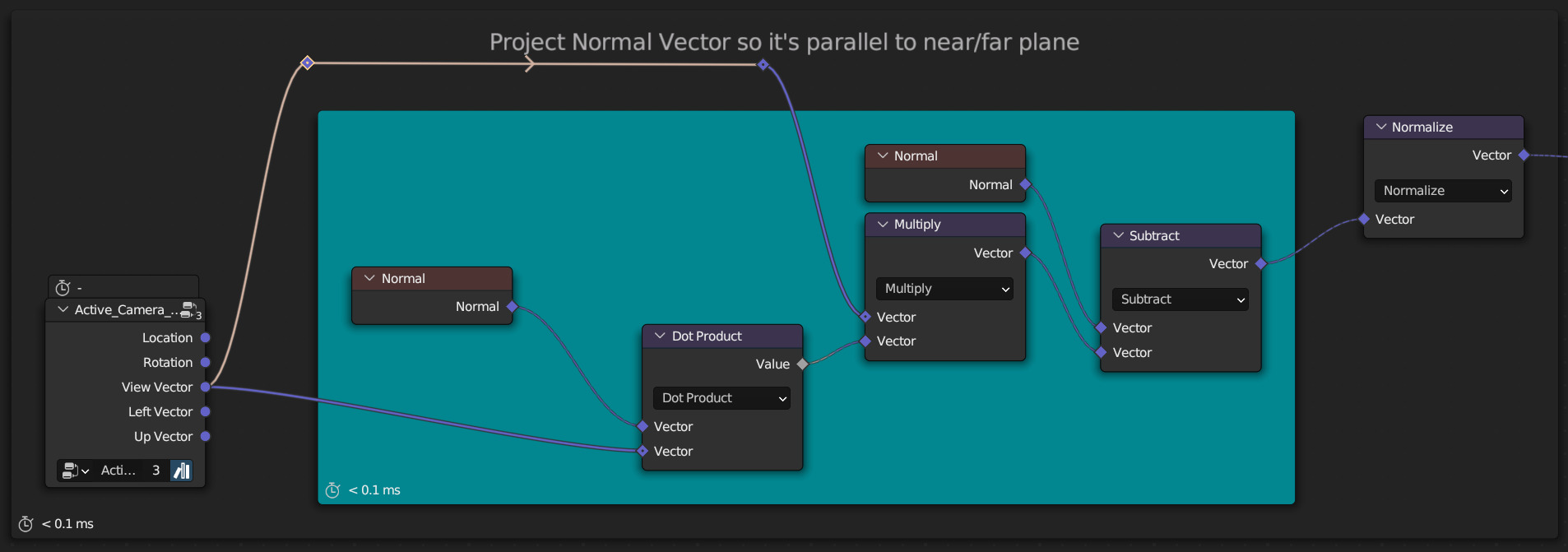

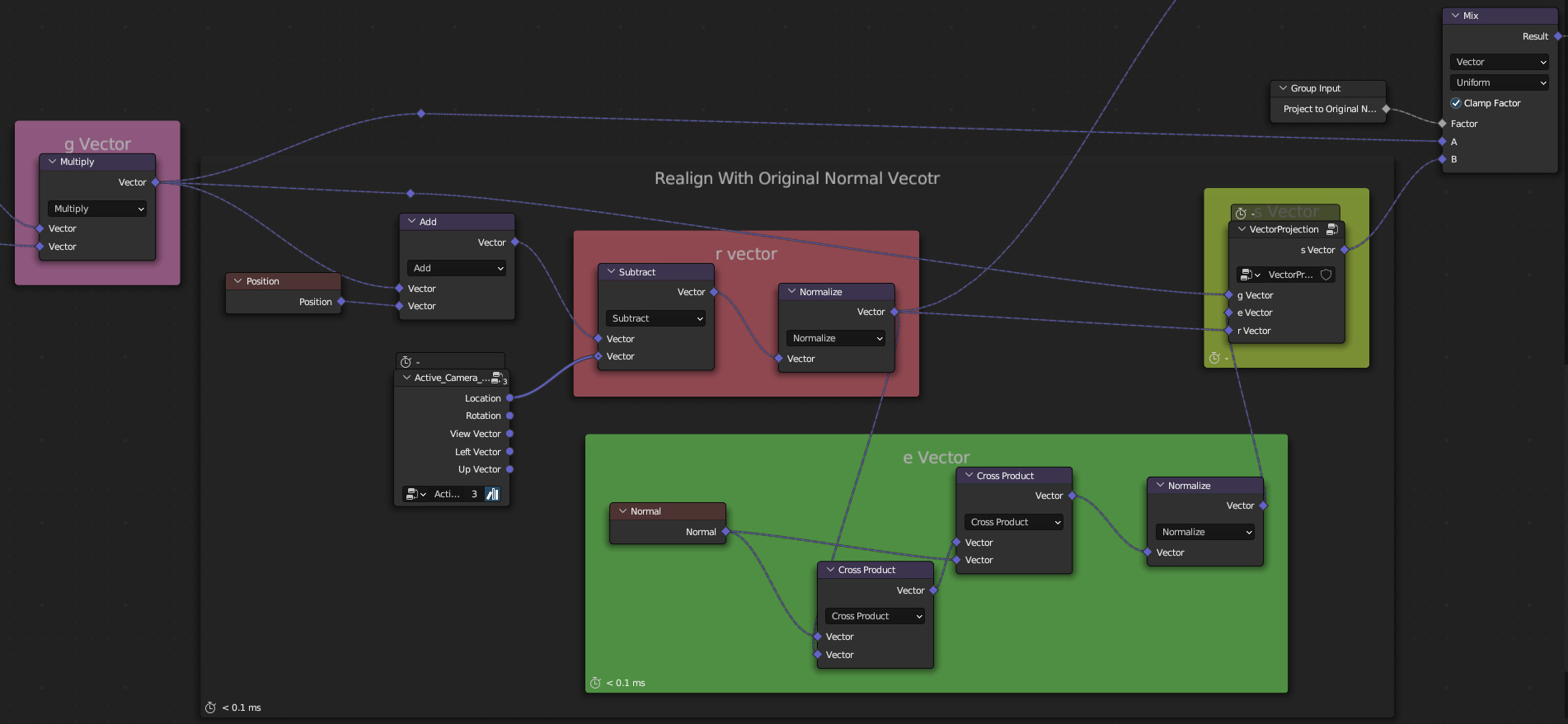

With that node group ready to go, we can now take the normal vectors of our mesh and project them to be parallel to the near/far plane of the camera, by projecting the vectors to a plane that has the view vector as its normal, or the plane orthoginal to the view vector.

Since both our mesh normal and view vectors are unit vectors, their dot product is simply cos(Θ). Now imagine a triangle where our mesh normal vector is the hypotenus, and a vector parallel to the near/far plane (vector A) and a vector parallel to the view vector(vector B) are its two other sides, with vector A and B being perpendicular to each other. Vector B would have length equal to cos(Θ). So we multiply our view vector by cos(Θ), and subtract it from the mesh normal vector to obtain vector A, the projection of the mesh normal vector onto the plane orthogonal to the view vector. We then normalize this vector to apply scaling later.

Calculate Camera view vector from (0,0,-1); the default camera orientation, then project normals to camera plane.

2. Scale Projected Normal Vectors in Screen Space

2a. First we calculate the world space length of X pixels in screen space at each vertex. Specifying pixel count works, but when render resolution changes so does the outline size, so I instead use a screen-space ratio option to preserve outline sizes regardless of the resolution.

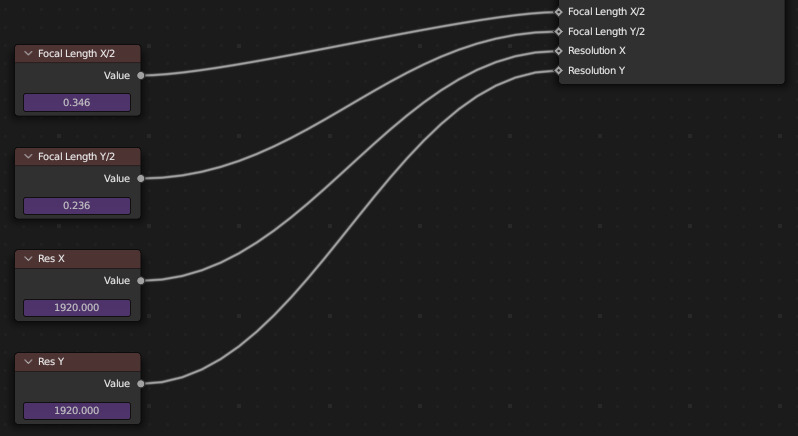

First we calculate the orthogonal distance from our camera to a viewplane that has a vertex point lying on it. We can then use the camera’s focal length to calculate how long and tall that view plane is in world space. With this and the scene’s render resolution, we can then calculate the length we want to extrude our inverted hull at any vertex such that they appear to be the same size in screen space.

![]()

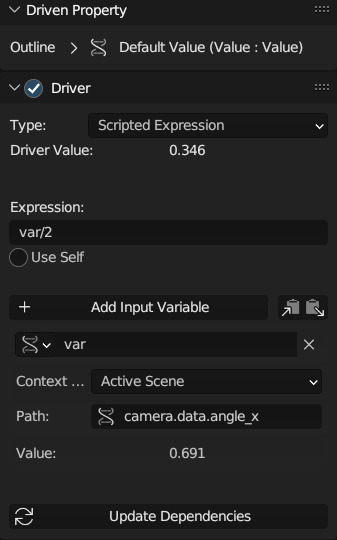

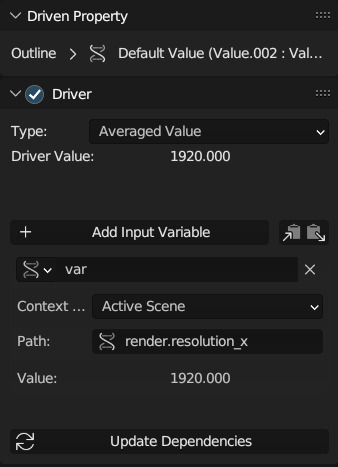

2b. To make the Outlines dynamically respond to changing camera parameters, we pass in the focal length and dimensions through drivers using context properties.

2c. What is mathematically correct isn’t necessarily what we want. Often, you’d want objects far away to have thinner lines, or have a line taper as it stretches into space. Thus, we must attenuate the value we computed in step 2a.

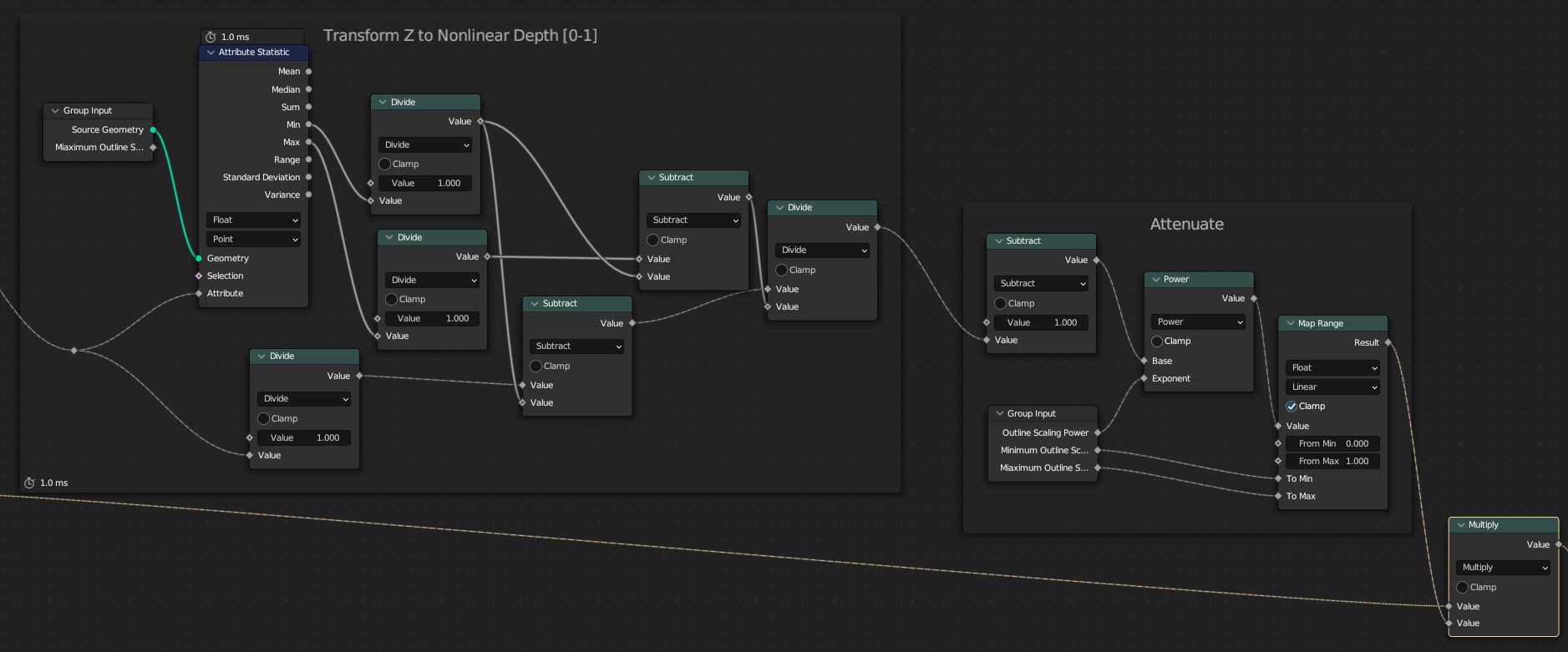

Intuitively, we would scale the values down based on its distance from the camera; we can use the previously computed length to viewplane value. However, this is pure linear Z value, meaning that if it’s re-mapped to 0-1, most of its values will lie on the upper range. Similar to how we must transform a Z buffer into a non-linear depth buffer, we must do the same here. Then we can attenuate it with a power factor, use map range to map a minimum value and maximum value for the outline, and finally multiply it with the value from step 2a.

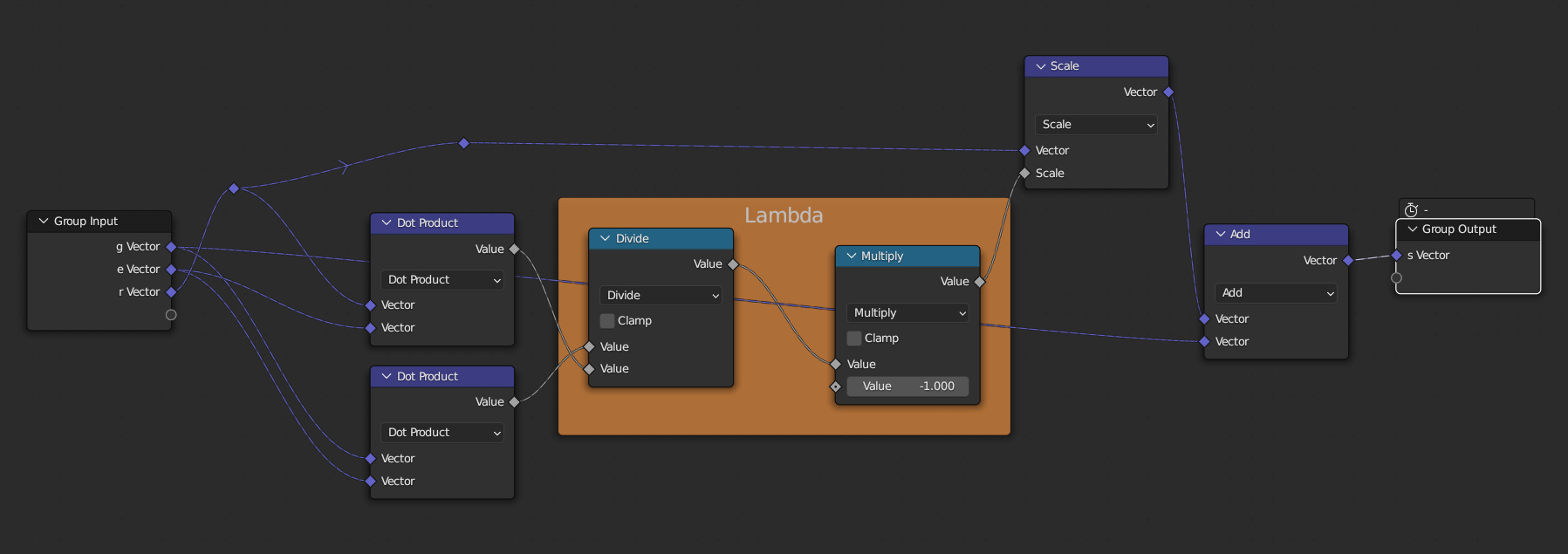

3. Re-Project Back to Original Normal Vectors

Because we’ve projected our normal vectors to be parallel to the near/far plane, when they are used to create the inverted hull, the hull may often clip the original mesh, causing artifacts. Therefore, we must reproject our vectors back to the normal vector, while preserving their screenspace size.

Check out this PDF for an explanation on projecting a vector onto a plane from any angle

Inside of the VectorProjection vector group

4. Final Steps

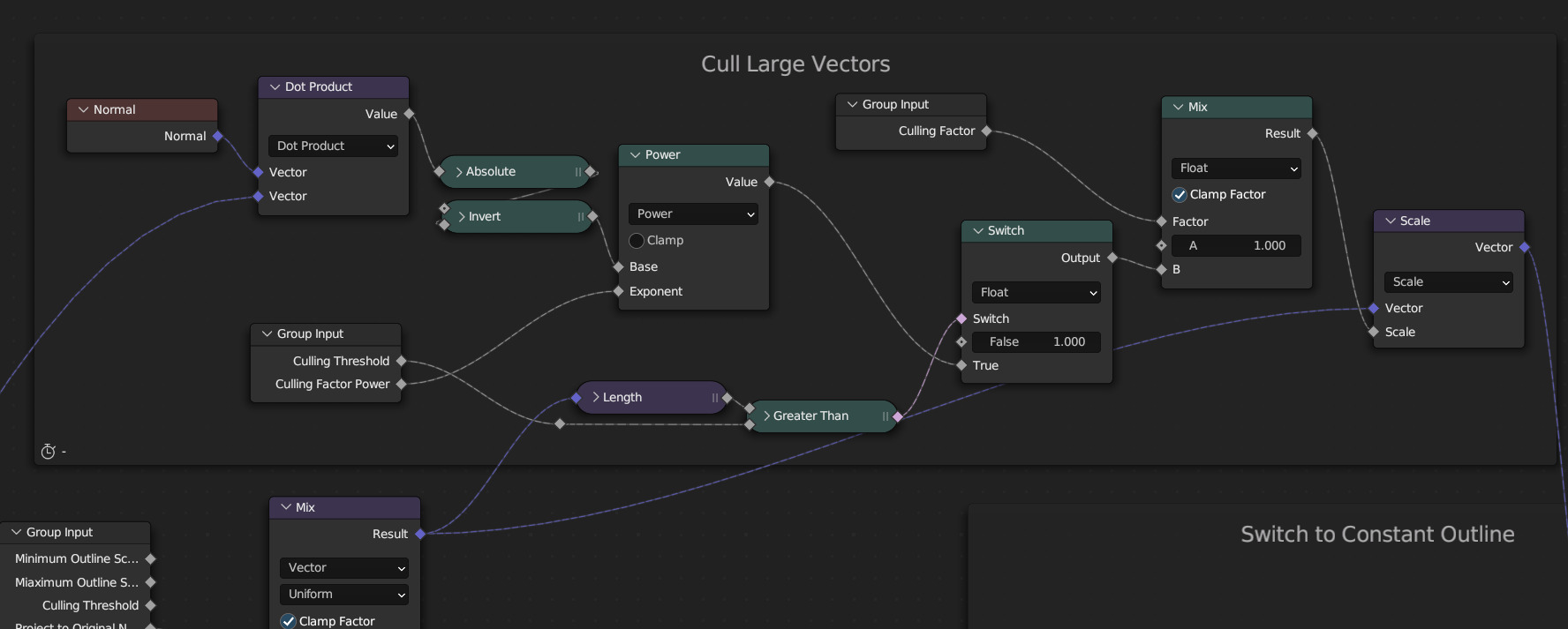

4a. We may see weird artifacts when the reprojected vector is close to being parallel to the vector from the camera to the vertex, because the reprojected vector needs to be scaled to a large degree after step 2 to be parallel to the original normal vector. So we must attenuate these vectors. Luckly for us, where these vectors occur also happens to be there the inverted hull is not visible, so we can simply scale them down.

We can do so by:

- Use the dot product of the g Vector and original Normal vectors to determine which vectors we need to cull. The more parallel they are,

- We do not care about direction, only parallel-ness, so we use the absolute value. This also makes the range of the values to be [0-1]

- We then invert the values, this makes it such that the closer a vector is to being parallel with the r vector, the closer it is to 0.

- Then use power to attenuate for non linear behavior

- Check if our vector from the previous step is greater than a given value, if false then change our attenuation value to 1 (do nothing).

- Mix with culling factor and scale our vector from the previous step.

Dot Product's input B is the g Vector, and B is the s Vector from 3

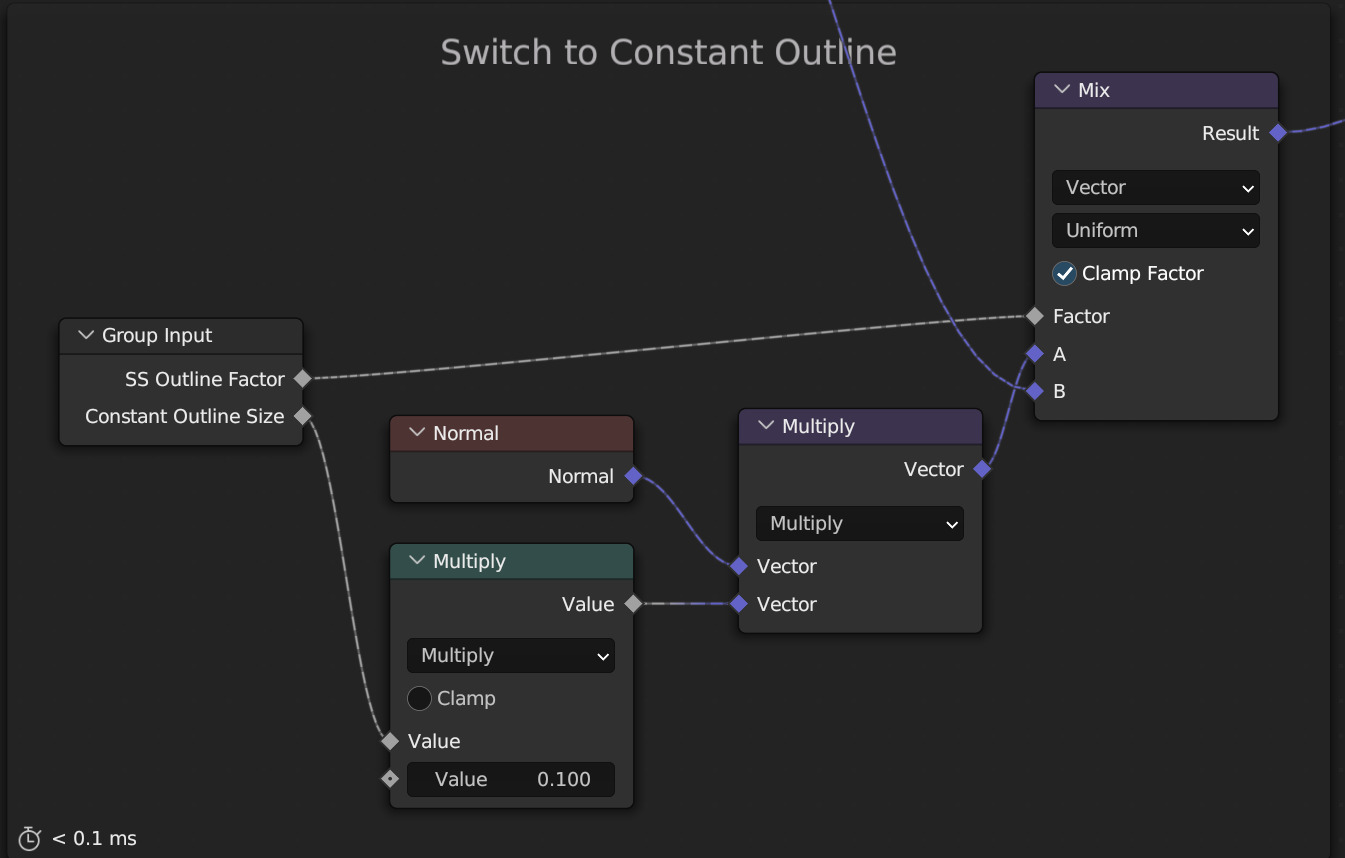

4b. We want to provide options for using and world space constant outlines and blending between that and screen space outlines, so we add the following nodes.

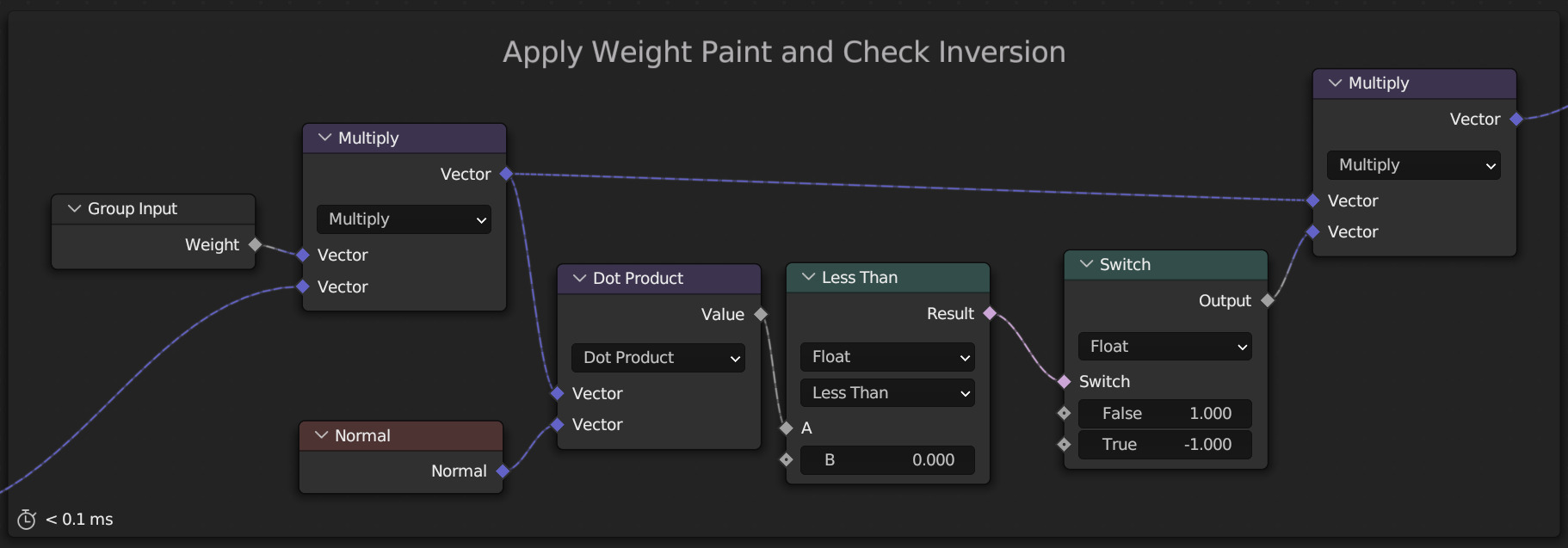

4c. We make use of vertex weights to allow further user attenuation of the outlines. Also, the re-projection may cause some vectors to point inside of the mesh instead of out, so we perform a dot product check and invert the vectors. This still preserves the screen space size of our outlines.

4c. We make use of vertex weights to allow further user attenuation of the outlines. Also, the re-projection may cause some vectors to point inside of the mesh instead of out, so we perform a dot product check and invert the vectors. This still preserves the screen space size of our outlines.

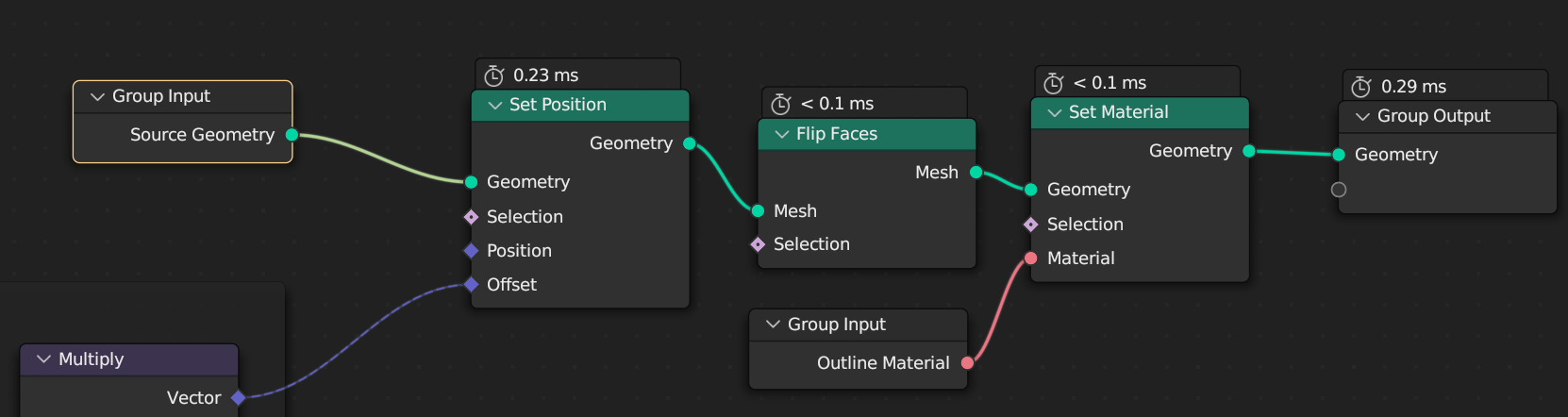

4d. Extruding our Inverted Hull then just involves giving each vertex the offset that we calculated, flipping its normals, and setting an outline material.

4d. Extruding our Inverted Hull then just involves giving each vertex the offset that we calculated, flipping its normals, and setting an outline material.

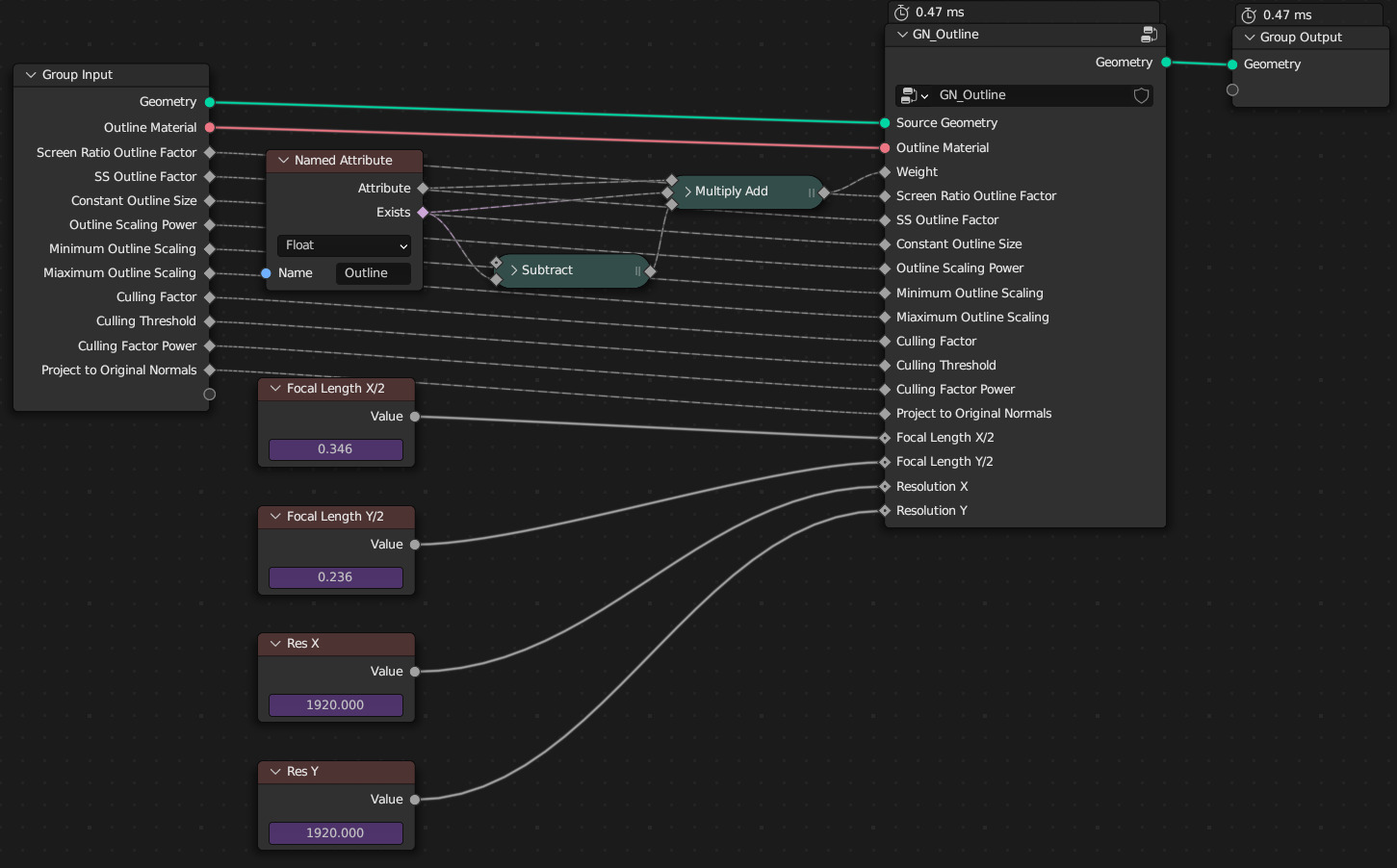

4e. Now all you need to do is to grab the weight attribute and connect it to the input of our node group, and link up all other inputs to the inputs of the outermost group.

2 nodes in between to default the weights to 1 if the attribute does not exist

Done!

And done! Now you have a geometry node group that takes a geometry and material, and outputs inverted hull outlines in screen space, with a variety of adjustment options, and can be readily linked to other files and use.

If you want to control the inverted hull of multiple mesh objects at once with this, nest it inside another layers of nodes, and use the top layer as the geometry node object for the modifiers of all desired objects.

Download

If you want a finished version of this project, you can grab it for free Here